Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) in Psycho, dir. Alfred Hitchcock (1960)

Psychosis is a loss of contact with reality that usually includes false beliefs about what is taking place or who one is (delusions). Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 thriller Psycho is an excellent depiction of psychosis on multiple levels. The anti-hero of the narrative, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), is famously diagnosed with multiple personality disorder at the film’s conclusion. As we learn, sometime before the film’s start he killed his mother and her lover, and now suffers from split personality disorder, sometimes believing himself to be her. It is possible that Marion’s suggestion, during her and Norman’s dinner together, that Norman’s mother be institutionalized, which causes him to murder her, dressed as his mother, while Marion is showering in a room at his hotel. In his mind, her suggestion can be equated with the suggestion that he be institutionalized.

The depiction of Marion’s murder incites a certain psychosis in the film’s viewer, as they watch the narrative of Psycho unfold. During the “shower scene,” Psycho‘s audience is led to believe that the Norman’s mother might have killed Marion, since that is what they saw; they don’t know this is impossible, because they don’t know that she is dead. This misbelief is reinforced by the subsequent sequence, which depicts Marion’s body being discovered by Norman, as if he had not killed her only moments earlier. The audience in this moment has lost contact with the diagetic reality of the film, led by false beliefs about what is taking place within the storyline and which characters are in fact being depicted onscreen at which time.

In Psycho, such aspects of induced audience psychosis extend to the construction of the plot itself. The film’s plot is initiated with a series of scenes during which Marion steals $40,000 and then skips town. Watching Marion guiltily pack her suitcase and flee, drive out of town, get questioned by a highway patrolman, then purchase a new car at a used car dealership she passes, the audience is led to believe that it is Marion’s theft which is driving the plot of the movie. This theft however becomes almost completely irrelevant once Marion gets murdered. Up until her murder the audience is in a certain sense psychotic since what they are led to believe is unfolding before them–the development of key plot elements–is not really what is taking place.

What one is kept from perceiving, as Psycho’s first few scenes unfold, is that that Marion’s theft is nothing more than a bait-and-switch. It is the theft which brings Marion, and the audience, to the Bates Motel, so that she can be murdered, and a series of very suspenseful and gruesome scenes can be portrayed. This narrative technique of bait-and-switch is known in film theory as a “MacGuffin.” Hitchcock himself popularized the term, which he defined in a 1939 lecture as ” the mechanical element that usually crops up in any story.” Interviewed in 1966 by François Truffaut , Alfred Hitchcock illustrated the term with this story:

It might be a Scottish name, taken from a story about two men in a train. One man says “What’s that package up there in the baggage rack?”, and the other answers, “Oh, that’s a MacGuffin”. The first one asks “What’s a MacGuffin?” “Well”, the other man says, “It’s an apparatus for trapping lions in the Scottish Highlands”. The first man says, “But there are no lions in the Scottish Highlands”, and the other one answers, “Well, then that’s no MacGuffin!” So you see, a MacGuffin is nothing at all.

(With this in mind, one is led to wonder if Hitchcock intends the lengthy scene of Marion packing–with its focus on her suitcase–and the extension of the trope of escape into the Bates Motel–whose name rhymes with “bait”–as a subtle, composite allusion his use of the MacGuffin)

The term MacGuffin also a history in the discourse of MOOC development. Stephen Downs, an instructor for the first Connectivism Massive open online course (MOOC) in 2008, has used the term MacGuffin many times (and as recently as July 9) to make the argument that content is an inherently secondary component of MOOC development. As Downs wrote on his blog, www.downes.ca, 7/9/13…

I have often said that content in learning functions as a McGuffin (or MacGuffin – you can spell it both ways) – you need it to drive the plot forward, but it can be almost anything.

Downes uses the term McGuffin to reinforce his belief about the centrality of social network formation, autonomy, and human interaction, to the success of MOOCs in facilitating online learning. Ideally, according to Downes, a MOOC is a sort of bait-and switch. For example: in 2008, Downes and George Siemens facilitated a course called “Connectivism and Connective Knowledge,” that was presented to 25 tuition-paying students in Extended Education at the University of Manitoba in addition to 2,300 other students from the general public. All course content was available through RSS feeds, and learners could participate with their choice of tools: threaded discussions in Moodle, blog posts, Second Life, and synchronous online meetings. In this MOOC, the idea of content–centered the epistemology that knowledge is distributed across a network of connections–was nothing more than an excuse to facilitate a network of connections organized around that content, through which students would learn more about education and the internet. That this should be somewhat tautological only reinforced the course’s bait-and-switch design: the network produced helped to facilitate learning about the content of the course because, by producing the network, students were learning-by-doing. Like the MacGuffin of Marion’s theft, idea of “content” with regards to “Connectivism and Connective Knowledge” is only a necessary mechanism intended to initiate a related, subsequent occurrence.

Like Hitchcock’s MacGuffin, Downes’ identification of the term McGuffin is predicated on a the perceived existence of a psychological complex whereby someone else has come to ascribe undue and supreme importance with a minor aspect of something witnessed in the process of becoming (for Hitchcock, story-line; for Downes, online courseware). To this end, Downes’ identifies the existence of the MOOC McGuffin of content as predicated on a certain psychosis, whereby a MOOC-maker believes they are developing a traditional, content-driven course, with the only difference being it is now offered in an online format known as “MOOC.” According to Downes, bad faith has negative consequences for learning outcomes. As Downes stated in his EDGEX2012 presentation,

[T]o the extent that a MOOC focuses on content, like a traditional course, it begins to fail. A MOOC should focus on the connections, not the content…when the structure of the course comes to be about this central concept or content, then the actual intent of the MOOC to distribute and democratize learning has been subverted.

To differentiate between the MOOCs which emphasize connections and those suffering from psychotic content override, Downes has identified two categories. Those that emphasize the connectivist philosophy Downes has categorized as”cMOOCs;” those that resemble more traditional courses, such as those offered by Coursera and edX, fall under the category”xMOOC.”

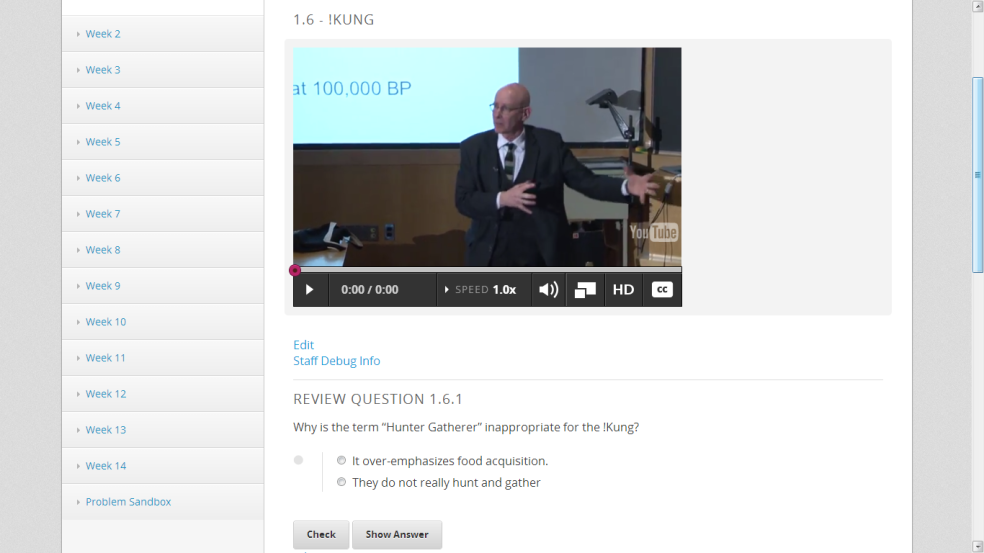

4.605x, as you might imagine, is an xMOOC. It is content driven. This at least in part because we are operating on a given, inherited platform–edX–which is optimized towards large scale, semi-interactive access to videos, readings, and problem sets. In addition to this material, the edX platform features a discussion forum component.

As an integral part of a team creating an xMOOC, I would like to reflect for a moment Stephen Downes criticism of content driven course development as a subversion of the democratization and decentralization of learning. Discussion forms an integral part of the 4.605x course package. The primary purpose of discussion in this course is to engage students in a meaningful manner to focus and reinforce key topics and ideas from Mark Jarzombek’s recorded lecture material A secondary purpose of discussion is to address technical questions about either course material or the online courseware environment. These primary and secondary purposes are addressed through two distinct types of discussion, discursive and troubleshooting, outlined below.

Discursive discussions are issued on a rolling basis, with lecture material. Sometime soon, our team will be responsible for viewing recorded lectures, and producing one, 75-150 word discussion prompt. This prompt will be issued in a “discussion” component, filed in a sub-unit, within each lecture, placed after the lecture material. The prompt will address the topic of respective lectures, through one of the following frameworks:

1) Asking students for further reflection or critique of a particular aspect of a particular building or topic discussed

2) Encouraging students to relate a particular item to a contemporary event or analog.

3) Soliciting personal experiences related to an item discussed in the lecture, or a particular theme.

These prompts will be released with each lecture, weekly. They will also be available within an aggregate discussion interface, where students will be free to post additional topics as they see fit.

Troubleshooting discussion will be initiated by students, and will be created by them to address questions they have about using the edX site and its associated materials. Specific questions about course content will be addressed here as well. Teaching Assistants will be responsible for addressing these questions on a regular basis. Student questions will be issued in the Discussion tab, under the topic “Troubleshooting.”

Now, Mr. Downes would be right to point out that that these uses of discussion emphasize Professor Jarzombek’s epistemological authority, to the effect of treating our courseware as a vehicle for sanctioned facts and narratives. Student input is essentially limited to questions about the format, with any other responses ignored (for now). Then again, to try and counter this aspect of 4.605x, as given currently, would mean to act in bad faith against the course’ content–even as one was trying to be faithful to a MOOC’s powerful capacity to facilitate novel, global connectivity in the interest of autonomous learning experience, of the cMOOC variety.

Survey courses, of which this is one, aggregate massive amounts of content into a singular, canonical format. Consider the first sentences of our course abstract, available on edx.org:

How do we understand architecture? One way of answering this question is by looking through the lens of history. This course will examine architecture through time, beginning with First Societies and extending to the 15th century. Though the course is chronological, it is not intended as a linear narrative, but rather aims to provide a more global view, by focusing on different architectural “moments.” The lectures will give students the appropriate grounding for understanding a range of buildings and contexts.

Appropriate and grounding are not terms which, when used in the context of pedagogy, could possibly lend themselves to the sort of McGuffin maneuver Downes idealizes. Survey courses are about a network of content, which is predetermined, and oftentimes not even by the person teaching the course. Survey courses rarely encourage students to create their own unique learning paths, and this is because they are generally instruments meant to discipline a students’ future learning, around a given corpus of sanctioned material. That said, given the specifically anti-hegemonic nature of Jarzombek’s architectural history–whose only consistent meta-narrative is that of “history” itself, as a concept–I am incredibly optimistic about this course’s ability to enable new connections to the field of architectural history, conceived in the broadest possible form. Indeed, I think that the global nature of the content we are now developing will help an unprecedentedly wide and diverse audience to relate to what has traditionally been an elite and Eurocentric topic. It is in this sense that our content is helping to decentralize, even if it is somewhat ambivalent about its missed opportunity to democratize.

In a challenge to Downes’ paradigm that “the content is the McGuffin,” I would like to propose that like cMOOCs, xMOOCs of the sort our team is now working on are also predicated on a type of baiting operation, but one which follows a layered feedback-loop rather than initiating a single, teleological process of connective learning. Rather than “bait-and-switch,” 4.605x is a “bait-and-bait.”

MITx, which hosts a few different course teams, like the one we are all a part of for 4.605x, also collaborates with the Teaching and Learning Lab and the Office of Educational Innovation and Technology to coordinate research on the use and effectiveness of emerging digital technologies. Through the open sharing of data generated by MITx projects, the team helps to stimulate research that will make the next generation of learning technologies even more innovative and effective.

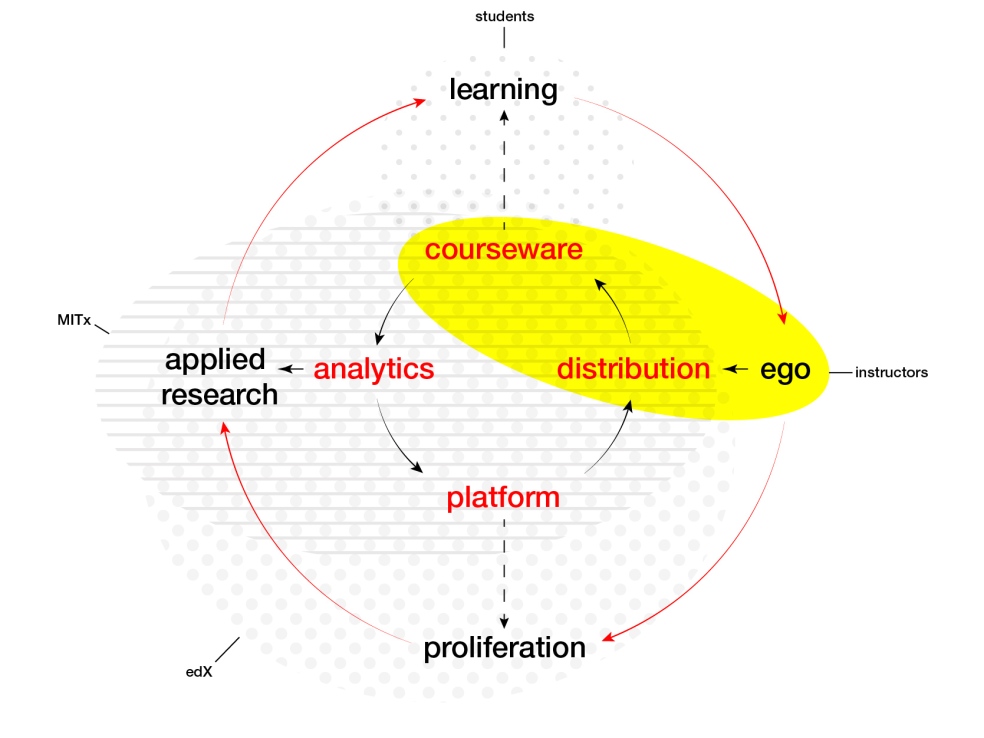

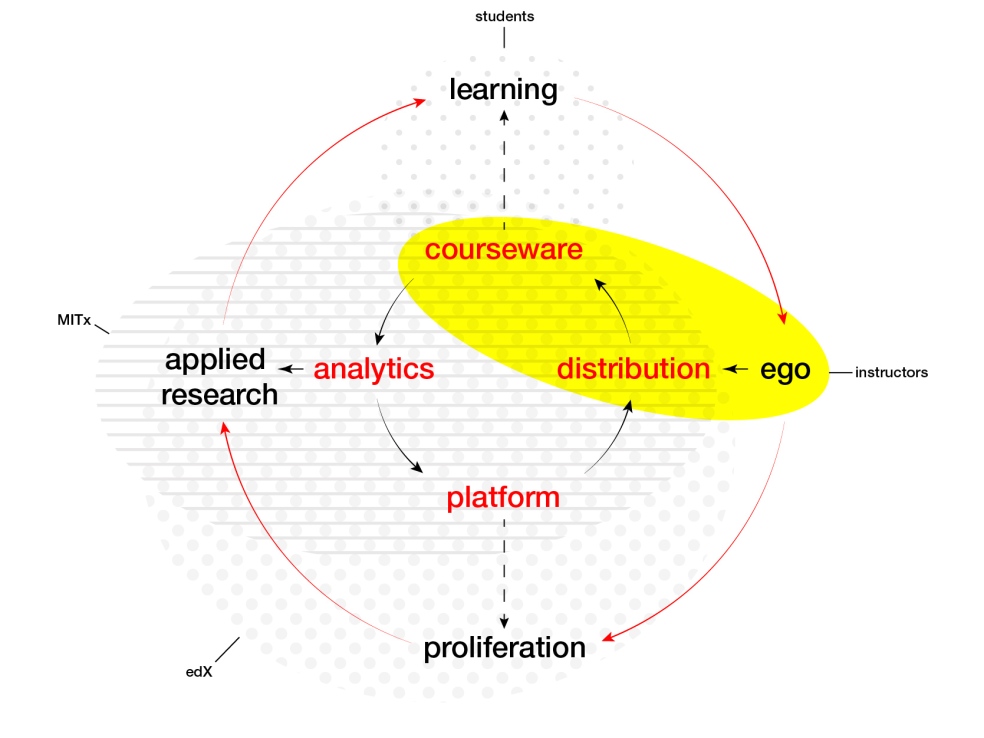

It is departing from this collaboration that I would argue that the bait-and-bait paradigm under which we at 4.605x are operating functions, as follows: courseware, guided by professors, developed at MITx on edX software, and hosted by edX, is essentially bait for enrolled students to facilitate analytics whereby demographic and aggregated click data (where did students click? how often? at what times? etc.) can be examined; thereafter, this research is applied to improve edX programs and to develop best practices for the production of courseware. In exchange for participating in this process, students receive access to world-class educational content which, we assume, they learn something from; the analytics help MITx and edX to, themselves, learn more about how the students are engaging with the material and platform provided, in the interest of improving upon that student learning experience. edX, which distributes many xMOOC offerings, can leverage their constantly-improving, high-quality software to encourage new partner institutions to produce and utilize xMOOCs on the edX platform–which feeds the production of more data, and more improvements, and therefore more partner institutions. It is the prospect of distribution, generally, which encourages instructors to facilitate the creation of xMOOC content, in collaboration with MITx. This desire might stem from institutional pressures, individual ego, or a sincere desire to teach as many students as possible–but for our purposes it is only important that there is some drive to long term benefit (or avoidance of negative outcomes), centered the prospect of knowledge distribution, which is fueling instructor participation in xMOOC production.

I have illustrated this relation of feedback loops in the diagram below. As you can see, MITx, edX, students, and instructors all participate in an nested, tautological circuits of knowledge production and distribution–although they engage with those circuits from different vantage points. In sum: content is bait for analytics, which feeds the production of better courseware; the prospect of improved courseware is the bait for the uploading and offering of content; the prospect of distribution is what feeds the production of content. Everything is a MacGuffin for a McGuffin, in one way or another.

bait-and-bait diagram

In this sense we, at MIT, are all like Marion Crane at the wheel: determined to head somewhere, but knowing that the fact that we are driving is less important than the opportunities offered by that fact, and what might develop, as a result. Should one only focus on any one particular territory within the bait-and-bait–on the instructor’s, for example–they might be misled into thinking that the xMOOC fails to take into consideration some of its potentials (optimized learning), while over-emphasizing others (content). From this vantage point it might look like we might suffer from the monolithic content override Downes warns against. This is short-sighted. 4.605x is inherently a network–but one with many different, autonomous layers. To the extent that a we might choose to focus on this network, as the driving force behind our courseware, like a cMOOC, we would lose sight of the pedagogical ambition of our course, which is to instill a certain historical methodology to as broad an audience as possible. While it decentralizes the distribution of that particular content, the goal in distributing that content is admittedly a little undemocratic. It’s a compromise; I’m OK with that.

–Samuel Ray Jacobson, MITx fellow